Alexa Drake

Credenza

Until I built my credenza, I had only built for function. I built my craft-table so that I would have a space to work on projects -- I planned to build a guitar-amp, and that would require a space where I could work with electronics and solder; and I rebuilt the deck in my back-yard, which had an in-dedk hot-tub sized hole in the middle of it, so that I could keep a container-garden separate from the rest of the yard. The credenza, though, started with an aesthetic design.

My living-room was bare at the time, and I hadn't quite decided on the layout of furniture; I didn't have any furniture except for the Ikea couch that I had had delivered on the day that I arrived from Wisconsin, that I slept on until my bedframe and matress arrived a month or so later. As such, the proportions of the design were more important than the precise measurements. As the first real piece of furniture to populate my living-room, this credenza would be an anchor for whatever vibe I wanted to create in my space.

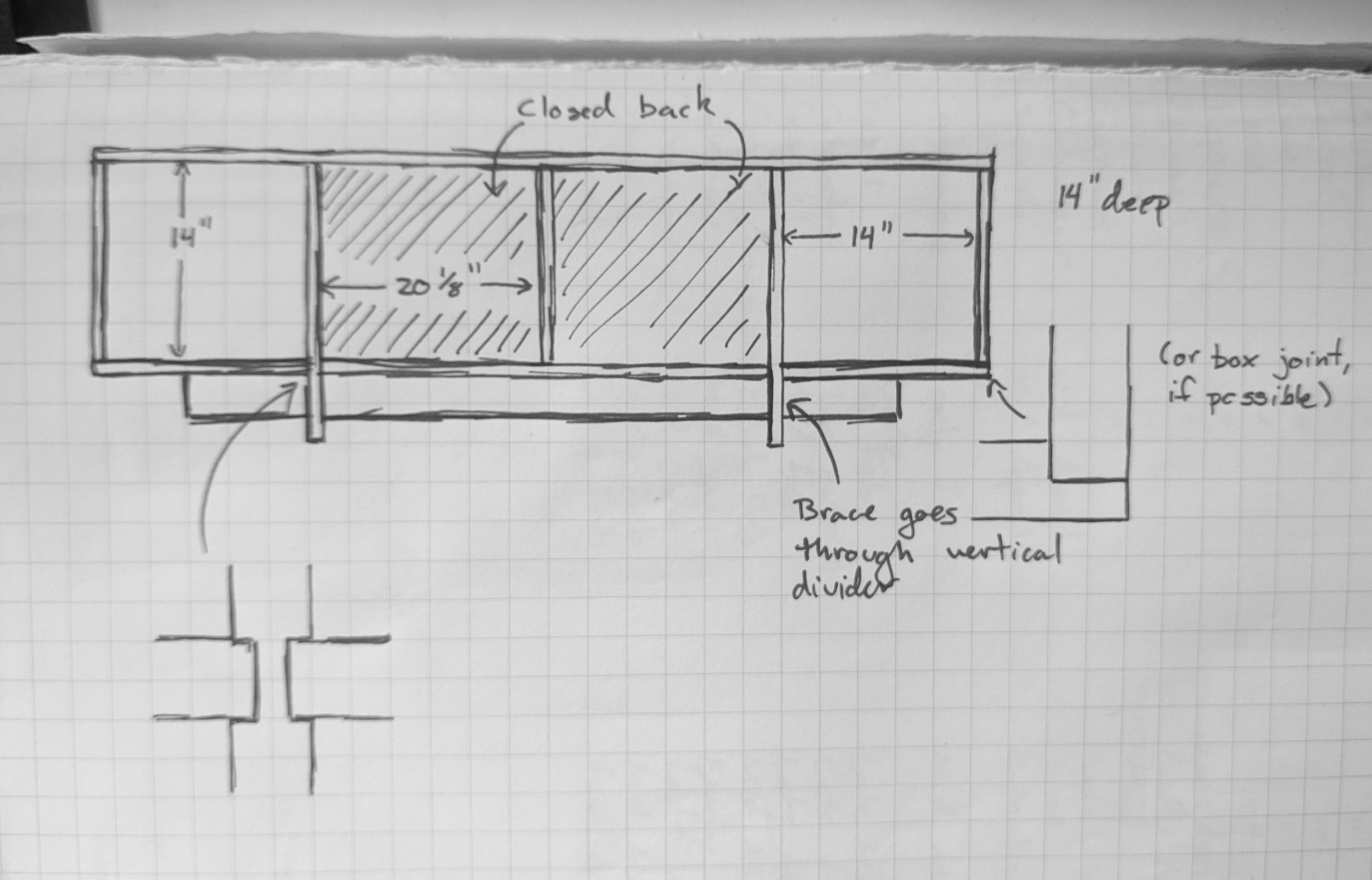

The design started from a function: furniture to hold a stereo-system and my modest record-collection. In addition to adding the structural strength to prevent the three-quarter inch pine boards (all of the lumber is 1x-stock; either glued into panels or, in the case of the shelf-support, glued into 2x-stock) from bowing under the weight of the records between the two-legs and to allow the shelves hanging off of the outside of each leg to support any weight at all, the support beneath the shelf lends a sense of visual weight--in much the same way that, when I worked at an art-supply store, designing and assembling picture-frames & mats, while attending community college, I would regularly position the image slightly above center because even margins sometimes appear imbalanced.

The two measurements that mattered most to the final design were 1) the space I chose for the credenza, and 2) the width of the stereo-system & records that I knew would occupy some amount of the credenza. Symmetry was an important part of the design, and while the whole thing had to fit into the space, at least one shelf needed to be wide enough to hold both the receiver and the tape-deck and tall enough to store records.

I have lived with this credenza for a couple of years, and my feelings about it have softened over that time. After the initial excitement of having this new piece of furniture, of having my record-collection available and organized, I started to notice the imperfections--and it is imperfect, as I am, still, very much learning the craft. Instead it is a snapshot of my skills at the time, an example of a project that I took from an idea to a finished product, and a reminder when I need it that I can still do things that I have not done before.

As I have gotten more comfortable with my tools I have considered re-building this design. I could hide the joints better with mortise-and-tenon joints. I could glue-up nicer panels (the panel-gluing practice that I got working on this project alone made a noticeable difference in the results, with the top, the last panel that I glued-together, aligned so closesly that I barely had to sand the joint at all) that would help me make cleaner rabbets and dados. And those are improvements I could make without new tools, and it's easy to think of improvements beyond those that I might make with "better" tools.

Since I left academia in 2016 I've earned my wage writing software, and early on I was privileged to work with someone who taught me that, in software, in practice (a word that is doing a lot of work here), nothing is really impossible. With version-control tools we can catch and fix mistakes we made in the past. Staging environments let us try things while keeping the stakes low. We can iterate, release features over time, adapt to changing needs and, when necessary, refactor old ideas into the foundation that will support even more software.

These are tools and practices and ways-of-thinking that do not necessarily apply to building furniture, at least not at the hobby-scale. A bad cut either needs to be incorporated into the design, accepted as-is, repaired (which may require additional material and will likely never be totally invisible unless painted, perhaps), or else the material is recycled (or scrapped). Lumber itself is not cheap (not in the way that compute is, anyway) and also comes at the expense of real, living, things that I love and respect--trees.

Perhaps the string that ties these two things-that-I-do together is this: the tools will only work as well as you use them.

I don't think I will re-build this credenza. This one is good enough for me, and it's a part of my woodworking journey, a journey that has no real destination; if I can't appreciate the journey, what will I have to appreciate?